On View November 26th – November 30th, 2025

Artist Bio:

In the United States, identity predetermines the paths of life that all of whom are within its borders will be forced to walk. Amongst the many factors that shape how society identifies an individual, race has long been the primary marker used in doing so. The simple act of being born into a specific race can (and does) effect how the world perceives and treats a person. The amount of dignity and institutional rights bestowed upon an individual varies within this convoluted racial stratum. The systemic distribution of rights reinforces the power structure, a structure which is dependent on the oppressed and oppressor dynamic. Erik Damien Escovedo has always found the concept of race a perplexing and troublesome issue, even at a young age, he realized there was a problem but couldn’t articulate it. As an adult he understands that racial classification was created for the purpose of dehumanization and exploitation, reinforced for the sole benefit of the colonial apparatus and its descendants. His art is an allegorical body of work, where he is attempting to communicate how normalized institutional racism has affected American Indians, while highlighting various traumas that settler-colonialism has brought down on two continents of Indigenous peoples for over 500 years. He hopes that his work will influence the viewer’s idea of representation and use of language as it pertains to Native Americans; perhaps even offer a good teaching on valuing humanity.

DISCLAIMER, he does not speak for all Indians and he only speaks for himself as an Indian. It seems that for people of color, they oftentimes find themselves playing the role of ambassador of their race, as if it were ever possible that an individual could be the wholly embodiment of an entire group. Though some may find his disclaimer pompous, and somewhat perplexing; he says it is perhaps their or the viewer’s own privilege that has afforded a blissful ignorance of such nuanced inconveniences. The intentional misunderstanding of Indigenous peoples was carefully engineered to racialize and consolidate their identities into one generic classification, erasing their histories, cultures, and relationship to place. He wants his art to be part of the ongoing conversation on how Native people reclaim everything that has been stolen, including their narratives. If the rest of western society properly perceived and understood American Indians, he may not have ever felt the need to paint images of American Indians.

As you may have noticed, he interchanges the labels American Indian, Native American, Indian, Native, and Indigenous people; all of which are correct and incorrect, depending on context. This language may be problematic for people, but he can tell you that this tradition of misclassifying Natives began when Columbus first “discovered” Indian country. It is also worth mentioning that he purposely interchanges labels in order to ignite dialogue, hoping that people come to realize that one of the big problems originated from not allowing tribal communities their right to properly introduce themselves with their own given name(s). They are from many nations, many cultures, and have many stories. His style of storytelling is done by making marks on surfaces.

He wishes to tell stories that challenge the use of romanticized and demonized characterizations of Native people. He feels that even within today’s society of Wokeness, individuals still don’t understand how most perceptions of Indigenous peoples are skewed, and it’s that distorted perspective which hinders a societal humanization of American Indians. This skewed view hinders some non-Native’s ability to be a proper ally, because they have not fully realized Indigenous humanity. This passive participation of dehumanization prevents them from grasping the true value of Native knowledge, which he feels is a crucial component to healing our damaged world.

One of his elders said that:

“The birds haven’t forgot how to be birds; the bear hasn’t forgot on how to be a bear. Why have humans forgot how to be human? It’s your job as an Indian, that while you’re in those institutions, you teach those people to remember how to be human beings. They don’t remember, and we’ve fought to never forget.”

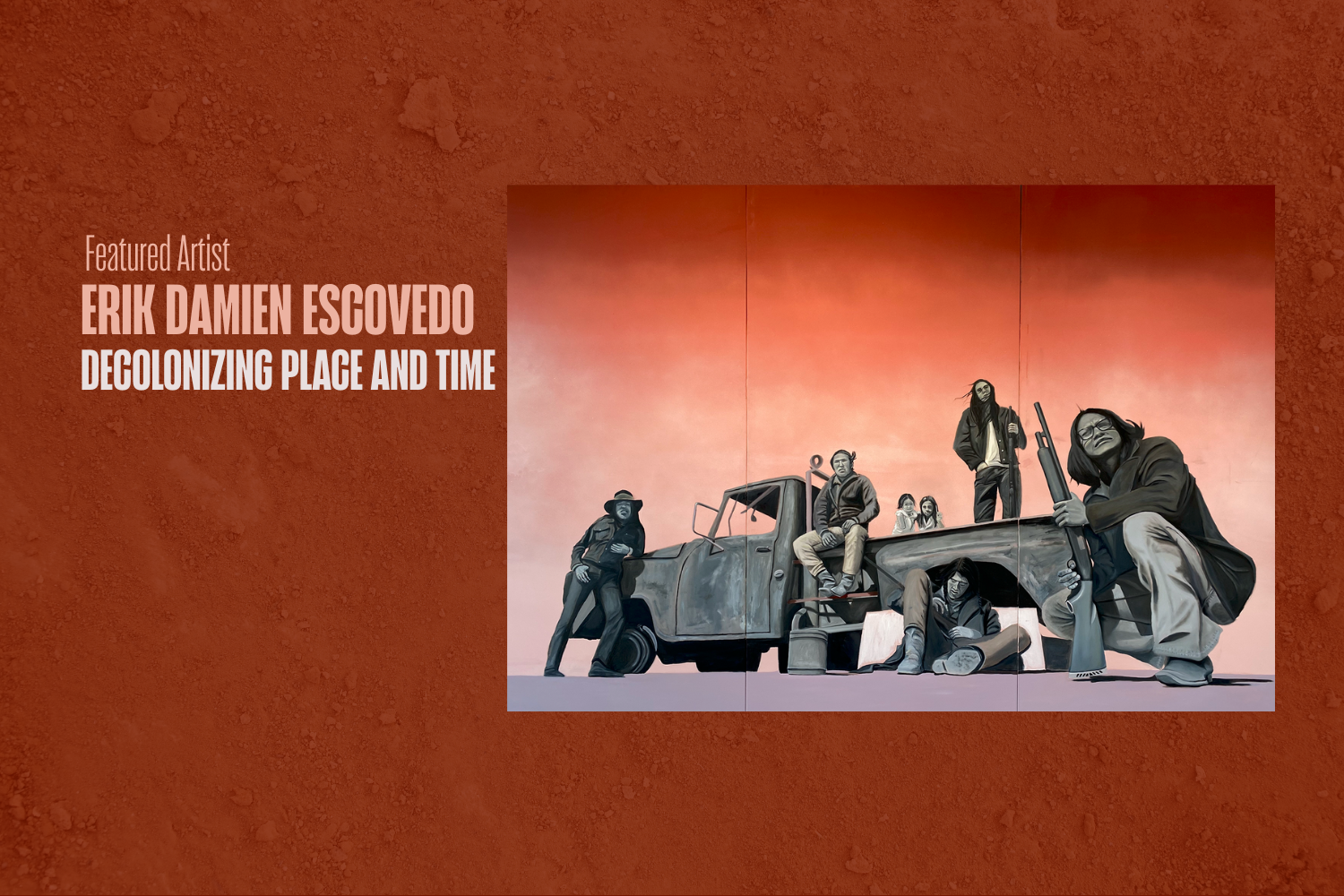

Decolonizing Place And Time

Relationship to place is of the upmost importance for Native American people. Our cultures, our history, our wellness, and our future are all tied into the lands that our ancestors have lived on since time immemorial. That relationship was drastically altered upon the arrival of Europeans in 1492. Since first contact, Native people have been in an ongoing struggle to maintain their relationship to place in order to ensure that land encroachment and Indigenous erasure eventually fail. The acts of occupying seized territories and fighting for tribal sovereignty demonstrate a tradition of perseverance that has been a part of Native American life for generations.

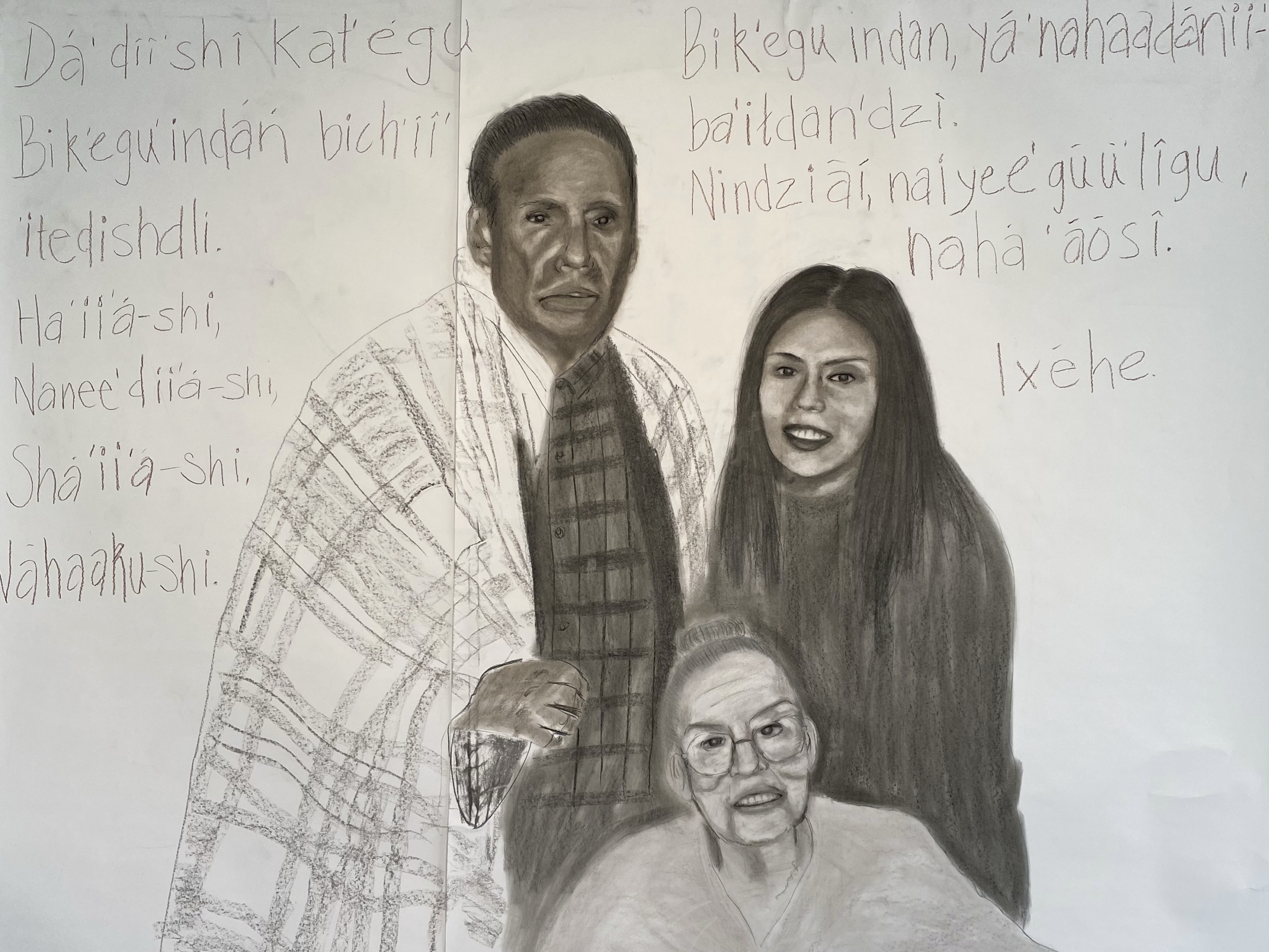

In my experience, when attending traditional gatherings, I am taught that our ancestors are with us and the past and present coexist. The intergenerational stewardship of land leaves physical traces of evidence proving to me that although the ancestors are not there physically, their spirits thrive through the continuance of ceremonial and cultural traditions. If the land is taken care of and continues living, then so do the people who crossed over.

Unfortunately, the traumas our ancestors experienced can also transcend time. The wounds inflicted by settler colonialism come from acts of genocide, displacement, forced assimilation, and broken treaties. The past manifests itself through issues like loss of identity, lateral violence, alcohol and drug abuse, suicide, and broken communities.

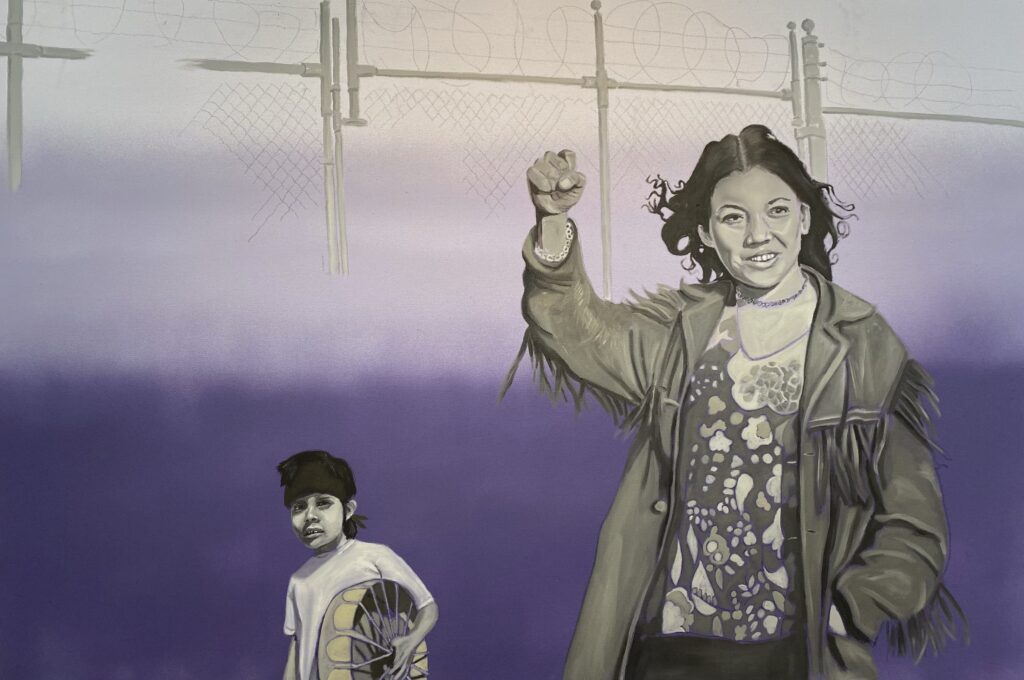

During the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Native American activists were standing up to the historical injustices that were still harming their communities. It was through these acts of Indigenous solidarity that we see Native people reclaiming places that carry both pre and post colonial legacies. Amongst the many events from this era of activism; I’ve chosen to paint pictures from the 1969-1971 occupation of Alcatraz (Ohlone traditional land), and the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee (Oglala Lakota traditional land). Organizers from both occupations cite the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 for justification of their actions.

It is with this invocation of the treaty that we see that these occupations do more than reclaim land rights, they also reclaim history. The legacies of place are decolonized by Native American activists working with the original stewards of the land to reestablish the places as Indigenous places, despite the scars of generational trauma.

In this series Decolonizing Place and Time, I am reappropriating photos from activists’ events and integrating my family photos together into the paintings to juxtapose the themes of pain and healing. The artwork illustrates different manifestations of intergenerational trauma my family has experienced as Native people and combines them with acts of resistance of settler colonialism. The work is my attempt to transcend time to recontextualize snapshots of my family’s history, while celebrating others that have successfully recontextualized place in the broader scope of U.S. history.